Chasing 6+ TB/s: an MXFP8 quantizer on Blackwell

We built an MXFP8 quantizer in CuTeDSL that hits 6+ TB/s on B200. The kernel writes scale factors directly into the packed layout that Blackwell's block-scaled Tensor Cores expect, so downstream GEMMs can consume them without an additional pack step.

MXFP8 is a microscaling format (from the MX OCP spec): instead of one scale per tensor or per row, it uses a more granular block-based scaling (typically 1×32). Each 32-element block shares a power-of-two scale exponent (UE8M0), while values are stored as FP8 (E4M3/E5M2).

What the kernel does

Input:

- X: fp16/bf16 matrix, shape (M, K)

Output:

- Q: FP8 E4M3 bytes, shape (M, K) (stored as int8 bytes)

- S: E8M0 (UE8M0) scale exponents, packed in tcgen05 layout

Quantization is block-scaled over 32 elements along K:

- For each row and each block of 32:

- a = max(abs(x[i])) over 32 elements

- Convert that block's magnitude to a power-of-two scale (UE8M0 exponent byte). The conventional target is:

- S ≈ a / 448 (448 is FP8 E4M3 max finite)

- rounded up to the next power-of-two so division is stable and dequant is cheap

- Quantize:

- Q = round_to_fp8_e4m3(x / scale) with saturation to finite

The key detail: we write S directly into the packed tcgen05-compatible layout, so downstream block-scaled matmuls can consume scales without a extra packing step.

TransformerEngine (TE) returns the same logical information: one UE8M0 exponent byte per 32-element block along K, stored densely as S_dense[m, kb] with shape (M, K/32). That's fine for standalone dequant, but block-scaled GEMMs need those same bytes in the packed tcgen05 layout. We skip that by writing packed from the start.

Measuring bandwidth

We report effective bandwidth:

Bw_eff = (2*M*K + 1*M*K + 1*M*(K/32)) / t

Read fp16/bf16 (2 bytes) + write fp8 Q (1 byte) + write S (1 byte for 32 value).

What worked on Blackwell

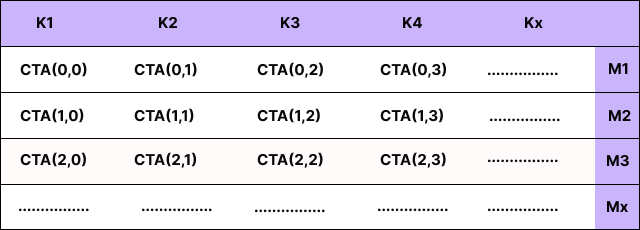

Tile the problem so the GPU has enough CTAs

Our first versions mapped a CTA to a block of rows and had it loop over all of K. Looks efficient on paper: good locality, fewer launches. But NCU showed Stall Wait dominating. Each CTA was too long-lived, and the GPU didn't have enough parallel work to hide latency.

The fix is structural: split over K in the grid.

- Pick two tile sizes:

- how many rows a CTA handles (e.g. 8)

- how much K a CTA handles at once (e.g. 256 elements)

- Launch a 2D grid over the M×K plane:

- cta_m = ceil_div(M, rows_per_cta) (tiles along M)

- cta_k = ceil_div(K, k_tile) (tiles along K)

- grid = (cta_m, cta_k)

Each CTA owns a rectangle: (rows_per_cta, k_tile).

Here's the intuition visually. Think of your input as a big M×K sheet:

If you don't split over K, you effectively have only one CTA column:

That reduces the total number of CTAs by ~ cta_k x and makes each CTA do more serial work.

Concrete numbers:

- Suppose =16384, K=16384

- Pick rows_per_cta=8, k_tile=256

- Then:

- cta_m = 16384/8 = 2048

- cta_k = 16384/256 = 64

- total CTAs = 2048 * 64 = 131072

If you don't split K, you only launch cta_m = 2048 CTAs. That's 64× fewer CTAs. On a big GPU, that's the difference between "lots of independent work to schedule/hide latency" and "the machine sits around waiting".

This single change was the first big jump in throughput (roughly ~1.3 TB/s → ~3.3 TB/s effective in our runs), because it fixed the "not enough work" problem before we touched instruction-level tuning.

Move HBM → SMEM with TMA, but keep it simple

Before TMA, we started with a very standard SIMT cp.async design.

In SIMT mode, threads move bytes:

- each thread issues some cp.async global→shared copies

- you commit_group / wait_group (or equivalent) to manage stages

- you do __syncthreads() -style coordination around shared usage

- then you do the SMEM→regs load, absmax/scale, and stores

In the OLD design (before K-splitting), the inner loop looked like this:

# OLD: CTA loops over all of K (too few CTAs, poor latency hiding)

for k0 in range(0, K, k_tile):

cp_async(...)

cp_async_commit()

cp_async_wait()

syncthreads()

smem_to_regs()

absmax_scale_quantize()

stores()After K-splitting, each CTA handles just one tile, so the loop body runs once.

Why SIMT plateaued

Even after tuning k_tile and stages, SIMT leveled off around ~3.4–3.6 TB/s for us. Once you're in that range, the kernel is no longer "dominated by DRAM bandwidth"; it's dominated by instructions per byte and overheads:

- copy bookkeeping

- synchronization

- shared replay penalties

On Blackwell, the obvious escape hatch is TMA bulk (Tensor Memory Accelerator) for the big HBM → SMEM move. The trap is over-pipelining TMA with repeated per-subtile barriers. That overhead eats into the gains. The version that stayed fast and stable was a simple single-bulk-load TMA design:

- one bulk transaction per CTA tile (load the full (rows_per_cta, k_tile) region)

- wait using the TMA transaction barrier (mbarrier) and then immediately consume

The kernel does three things per tile:

- TMA loads the tile from HBM into SMEM

- Compute: absmax, scale exponent, quantize (per row, per 32-element block)

- Store Q (wide) and S (packed, with alignment guard)

We avoided a "load subtile / barrier / compute / repeat" inner loop. That repeated barrier cost dominates once you're close to saturation.

Inside the kernel

With the launch geometry and HBM→SMEM path sorted, the rest is a tiled load, a per-row quantization loop, and stores.

CTA shape and thread mapping

Quantization is row-wise and block-scaled over K, so the natural unit of work is:

- a row

- and a 32‑wide block along K

With 128-bit loads from shared memory:

- each lane loads 16 bytes = 8 fp16 elements

- a 32-element block needs 4 lane

- with 32 lanes per CTA, that's 8 rows processed in parallel

We tried other configurations. This one had the best tradeoff between instruction count and occupancy.

The hot loop: "SMEM → regs → absmax → scale → pack FP8"

Pseudo-code for one CTA (simplified):

# Each CTA owns one tile: rows [m0, m0+8), K [k0, k0+256)

# 1) HBM -> SMEM (single bulk load)

tma_load_async(smem_X, gmem_X[m0:m0+8, k0:k0+256])

tma_wait()

# 2) Consume per row, per 32-element block

for row in range(8):

for blk in range(8): # 256 / 32 = 8 blocks

# load 32 elements from SMEM (vectorized across 4 threads)

x = smem_load_32(row, blk) # length 32

# absmax (done in integer domain for speed)

a = max(abs(x))

# scale = 2^ceil(log2(a / 448)), stored as UE8M0 exponent

ue8 = to_ue8m0(a / 448)

# quantize: q = round_to_fp8(x / scale)

q = fp8_e4m3_satfinite(x * inv_scale(ue8))

# store 32 Q bytes + 1 scale byte (packed layout)

store_q(row, blk, q)

store_scale(row, blk, ue8)Scale factors: dense vs. tcgen05 packed

The quantizer produces two outputs:

- Q: FP8 E4M3 bytes, shape (M, K)

- S: one UE8M0 exponent byte per 32 values, logically (M, K/32)

If you only ever dequantize in a normal kernel, you'd store S densely as:

- dense S: S_dense[m, kb] where kb = k // 32

But Blackwell's block‑scaled Tensor Core path does not load S from a dense (M, K/32) matrix. It expects scale bytes in a hardware-defined packed layout (CuTeDSL models this via BlockScaledBasicChunk / tile_atom_to_shape_SF).

So we write:

- packed S: the same logical bytes, but physically arranged in the tcgen05 format so GEMM can consume them directly (no reshape/permute/packing kernel).

Where this matters in practice is when you want to feed (Q, S) into a block‑scaled GEMM.

TransformerEngine's MXFP8 quantizer returns the same logical scales (one byte per (m, kb)), but it stores them in the dense (M, K/32) layout. A tcgen05 block‑scaled GEMM, on the other hand, expects those scale bytes in the packed tcgen05 layout.

So "packing" here means a real data reorder/copy: taking S_dense[m, kb] and writing the same bytes into the packed tcgen05 arrangement so GEMM can load them directly.

The bottleneck we didn't expect

After getting TMA and compute tuned, NCU still showed poor store efficiency. The problem: scale-factor stores.

NCU told the story in three steps:

- Memory Workload Analysis flagged low store utilization:

- low average bytes/sector for global stores when scale bytes were written as scattered byte stores

- SourceCounters showed significant "excessive sectors" on global traffic.

- SASS correlation identified the culprit:

- STG.E.64 (good): Q stores

- STG.E.U8 (bad): S stores as individual bytes

Writing 1 byte at a time sprays partially-used 32B sectors. Memory transactions pile up, and the scoreboard stalls waiting for them.

Our fix was the pack four scale bytes into a single 32-bit store when the address is 4-byte aligned. Fall back to byte stores otherwise. This dropped instructions and improved DRAM throughput.

Other optimizations

- Instruction-count cuts: Once TMA was stable, the kernel became sensitive to instructions per byte. The wins were mostly boring math hygiene, but they added up:NCU showed instructions dropping from 97.9M to 78.9M across these changes.

- Replace FP32 division with reciprocal multiply (x / scale is expensive if it compiles to fdiv)

- Fuse scale math into FMA: fma.rn.f32(absmax, 1/448, eps) instead of separate multiply + add

- Rely on the pack instruction's built-in saturation instead of explicit clamps

- Use packed FP32x2 ops for scaling (halves the scalar instruction count)

- Compute absmax in the integer domain: clear sign bit, integer max, convert to float once at the end

- Smaller CTAs: 32 lanes worked better than 64 or 128 for this kernel. More CTAs in flight, better latency hiding.

- What didn't help: We tried aggressive shared-memory swizzling to reduce bank conflicts. Conflicts went down, but the extra index math ate the gains. At some point you're just moving the bottleneck around.

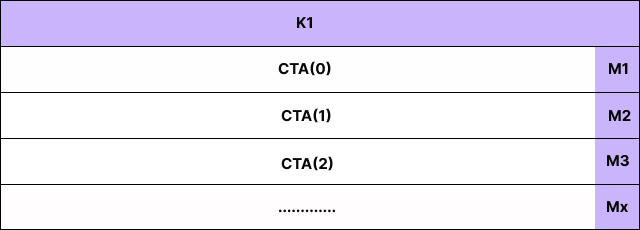

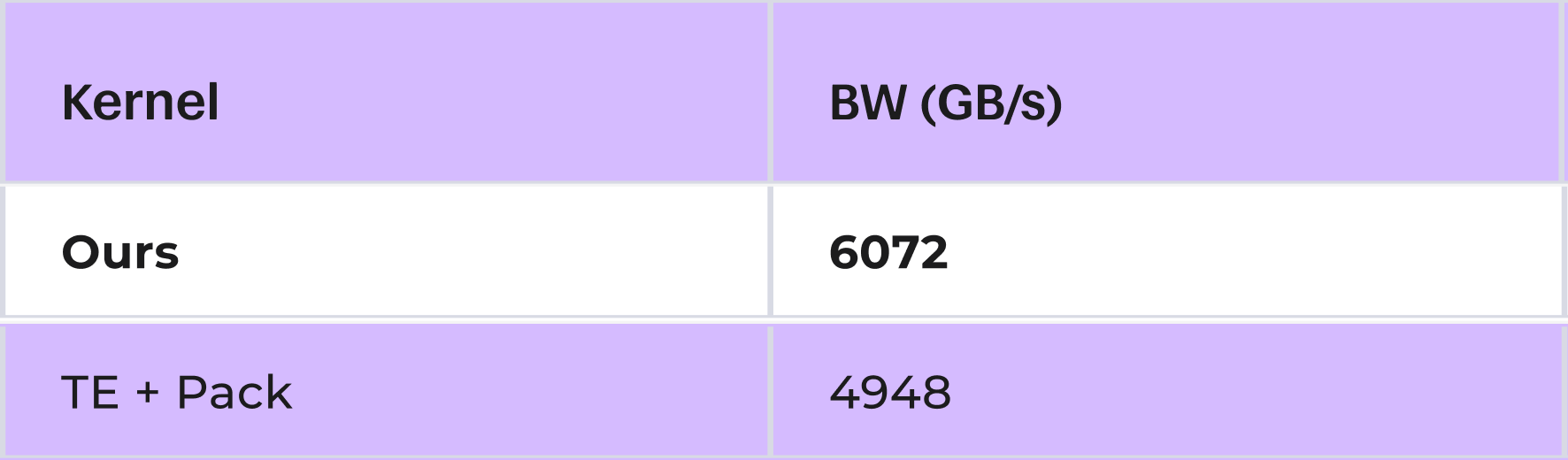

Results

On large shapes, our kernel sustains 6+ TB/s effective bandwidth while writing scales directly into the tcgen05 packed layout:

TransformerEngine's quantizer returns dense scales, so "TE + pack" includes the time to pack them into tcgen05 layout. Our kernel skips that step entirely.

Acknowledgments

This work was inspired by Cursor's kernel engineering blog.